New York Right-to-Repair Law Promises Easier, Cheaper Electronics Repairs

It's the first comprehensive right-to-repair law of its kind

Let’s call it a good first step.

On Dec. 29, right before the beginning of the new year, New York Gov. Kathy Hochul signed the Digital Fair Repair Act, a law that should make it easier for consumers to repair certain electronic devices, including laptops and smartphones, thereby saving money and reducing harmful e-waste.

The law, which had been awaiting the governor’s signature since it was passed by the state legislature last June, compels manufacturers doing business in the state to make repair parts, tools, and documentation, including schematics, available to the public, something companies had not been required to do in the past. It goes into effect on July 1 of this year.

This, consumer rights advocates say, should increase the availability of electronic device repair and bring down prices. Until now, independent repair businesses haven’t always had the tools and information they needed to fix broken devices, forcing consumers to go back to the manufacturers for repairs or to just buy replacements. The new law is meant to increase competition for repair work—and let consumers fix their gadgets themselves, if they feel technically capable of doing so.

What Devices Are Covered by New York's Right-to-Repair Law?

The law covers electronic devices purchased at retail, including devices popular with consumers like laptops, smartphones, and tablets.

It does not apply to so-called white goods, an industry term that typically refers to big appliances like refrigerators and washing machines. Nor does it apply to agricultural equipment like tractors—farmers, who were some of the earliest supporters of the right-to-repair movement, will still have to have this equipment repaired by the manufacturer.

And because the law only covers electronic devices purchased at retail, it’s unclear if, say, Chromebooks purchased by school districts would qualify. That raises the question of why these laptops should be treated any differently than a laptop purchased at a local store. Laptops purchased by small businesses directly from a manufacturer would similarly not be covered by the law.

Gordon-Byrne, of The Repair Association, says that the language of the law is vague enough that manufacturers of some devices, including TVs and video game consoles, may try to argue that they’re not covered by it. She expects to see manufacturers and the state go back and forth over the coming months to clarify this point.

Because the law goes into effect on July 1, a laptop purchased at retail today would not necessarily be covered. Of course, there’s nothing stopping a manufacturer from voluntarily providing parts and documentation for devices purchased before July 1, but they would not be required to do so.

It should also be noted that, at the prodding of consumer rights advocates, several of the largest consumer electronics companies, including Apple, Google, and Samsung, have already created self-repair programs, allowing consumers and independent repair shops to obtain parts and documentation.

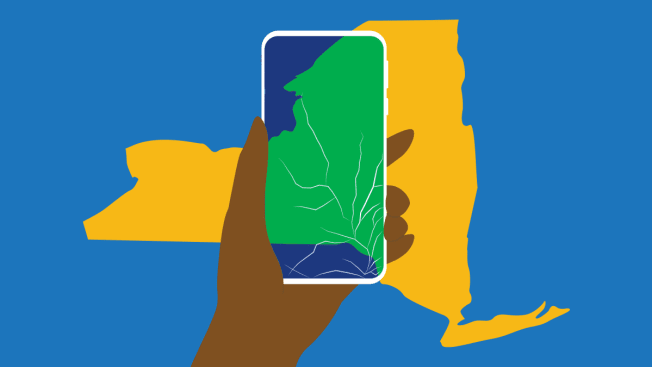

What If You Don’t Live in New York?

The answer to this question remains unclear.

When Massachusetts passed an automotive right-to-repair law in 2012, it effectively became the law of the entire country, with car manufacturers complying with its provisions. Similar to the Digital Fair Repair Act, these provisions required car manufacturers to provide parts and documentation to independent repair shops—which is why you can get your car fixed today at a local mechanic and not only at an authorized dealer.

So what will happen when, say, a resident of Texas or California attempts to obtain repair parts for their laptop after the Digital Fair Repair Act goes into effect?

Consumer Reports contacted several industry associations asking that very question, hoping to gain at least some insight into manufacturers’ thinking on how the law might impact residents of other states. These associations include TechNet, CTIA, the Consumer Technology Association, and the Internet Coalition, all of which were involved in the lobbying process.

Not a single association responded to our request for comment.

Consumer rights advocates are divided on how they expect manufacturers to respond.

Wiens of iFixit tells us it doesn’t make sense for manufacturers to create the infrastructure required to comply with the law, such as the ability to receive orders for repair parts, only to then restrict access to residents of New York.

Meanwhile, Nathan Proctor, who leads the right-to-repair efforts at the U.S. Public Interest Research Group, says he can "100 percent see" manufacturers not extending the ability to obtain repair parts and documentation to residents of other states, citing industry pushback to a recent right-to-repair law covering powered wheelchairs in Colorado.

“There is a difference between a small wheelchair manufacturer and a large consumer electronics company that has to balance its brand reputation,” he said. “But I expect to see this issue come up.”

What Comes Next?

Consumer rights advocates are keen to stress that just because New York passed a right-to-repair law, that doesn’t mean that their work is done.

Wiens says he expects some 20 right-to-repair bills to be introduced at various state legislatures over the next month or two.

Some of these bills will cover everyday consumer electronics devices like laptops and smartphones, while others will cover agricultural equipment or other heavy machinery.

The Federal Trade Commission in 2021 already endorsed the idea of right to repair, and one federal right-to-repair bill was introduced in Congress last year, but Wiens expects the fight to repair the stuff that you own to primarily be fought at the state level.

“There’s a real opportunity for this to get done in multiple states,” he says. “Different states will tackle different parts of the problem, creating a sort of tapestry of regulation that protects your rights.”

Momentum is also growing overseas, with right-to-repair legislation recently being introduced in the European Union and India. This, advocates say, is no coincidence, as more consumers are becoming aware of the issue and wondering why they face restrictions on products they’ve paid for.

“We aren’t trying to win any backroom deal just to sneak through a law,” says Proctor. “We are trying to win the public and the idea that people should and must be able to fix the things they own.”